The State Oversight Academy’s blog, State Oversight Matters, tackles the importance of congressional oversight; practical matters in conducting investigations, holding effective public hearings, and working together to find the facts; and specific topics requiring oversight such as appropriations, corrections, foster care, and more.

Building a Masterclass for State Legislators and Staff

In the Motor City last week the State Oversight Academy (SOA) rolled out an on-demand masterclass titled Introduction to State Legislative Oversight. The class is available on the SOA’s website and YouTube, and clocks in at just over 35 minutes.

When the SOA walked into the shop to build this new masterclass, there were already some useful tools and manuals in the garage. The SOA Wiki, the Checks and Balances in Action – Legislative Oversight across the States research, and experience building other oversight workshops helped us create something new, but still distinctly familiar for the Levin Center and informed by our team’s decades of experience in legislative oversight. If you’ve joined us for an SOA workshop before, then you probably noticed similarities with the featured content among the new state oversight examples and graphics.

When building the new state examples, we labeled each one using the avenues of state legislative oversight: analytic bureaucracies, appropriations, committees, administrative rule review, advice and consent, and monitoring contracts. To tune up the current material, we needed to use tools from all six avenues to explain how to address problems in states through legislative oversight.

Each example has three components: problem, oversight avenue, result. We searched Levin Center research, recent news, and notes from our conversations with legislative leaders across the country to find some of the best examples of legislative oversight and fact-finding work making a difference and yielding results. In the New York State Senate, for example, their Investigations and Government Operations Committee investigated and published a report on the secondary ticket market. We used the problem, oversight avenue, then results framework here. The problem is obvious to anyone who has purchased (or, in the case of the Taylor Swift show, tried to purchase) live event tickets. Hidden fees, an inability to secure a refund to postponed events, and bots outbuying regular fans at lightning speed to sell tickets at an unfair profit are just some of the recurring problems within the industry. State Senator James Skoufis, the committee chair, led a year-long investigation into these issues and published a report on the findings. This is a clear example of using the committee oversight avenue to examine a problem.

The result was Senate Bill S9461 during the 2021-2022 session, which passed unanimously and enacted several reforms including full ticket price disclosure prior to purchase, civil penalties for using ticket purchasing software, and refund policy transparency requirements in case of cancellation or postponement. This is a strong example of the committee avenue of oversight and how the tools in the committee oversight toolbox can help solve problems.

Sometimes, issues require continued monitoring after a tool is used to potentially fix a problem. The same is true with oversight, and especially emergency powers oversight. When building the advice and consent portion of the masterclass, we noticed many states recently reformed their emergency powers oversight. The pandemic resulted in many states reaffirming their oversight authority on emergency powers. Reforms limiting how long an emergency declaration may remain in force without a vote of the legislature, requiring the calling of a special session, and enforcing restrictions on curtailing rights like freedom of the press. Many of these reforms are new and untested. The SOA will be ready to monitor their use and results.

The SOA is already planning future classes. Stay tuned here for classes on juvenile justice, insurance fraud, and other topics. For now, please offer us any feedback on our first class at levincenter@wayne.edu.

We Make House (and Senate) Calls

Last week, the Levin Center conducted its 18th Congressional Oversight Boot Camp on Capitol Hill, in partnership with the Project on Government Oversight (POGO). The Boot Camp is a dense, two-day program. It covers everything from the historical and legal basis of legislative oversight to the practical details of putting together a media plan for a hearing, and it is packed with lectures from experts and interactive exercises.

Since our founding, these workshops have been a hallmark of the Levin Center’s programming. As the State Oversight Academy ramped up over the last year, we built and offered oversight training inspired by the congressional boot camp to state legislators and the people serving them. Our team has traveled across the country – on planes, trains, automobiles (and at least one rental bike) – to speak with legislators and their staff, present at policy conferences, and even provide committee testimony.

So, what happens in a State Oversight Academy workshop? It’s a little different every time. It depends on the length of the program, the interests and experience levels of the group, and the specifics of the state. In general, though, it goes something like this:

When we visit a state legislature, we like to start the program with the people we call “oversight partners”: auditors general, legislative research staff, ombuds, and so on. (As a reminder, you can find your state’s oversight partners on the State Legislative Oversight Wiki.) Bringing in oversight partners is a way to introduce state legislative oversight with local expertise and rich institutional knowledge. It helps participants understand the tools at their disposal and puts faces to names in governments that often work through email. It is also a great opportunity for presenters to showcase their work to legislators and offer context around recent oversight efforts from other corners of government.

After hearing from local experts, State Oversight Academy instructors take the stage for a presentation on the basics of legislative oversight. There is a lot of material to cover – everything from a history of oversight and its legal basis to the practical details of bipartisan cooperation on investigations. Along the way, we bring in stories from oversight work across the country, best practices backed up by the latest research, and much more.

During shorter workshops, we follow the presentation with an exercise to give participants hands-on experience with the material. At a recent workshop in Delaware, participants worked on an oversight plan in the wake of a fictional hurricane, deciding what information they would need to get, the tools they could use to find it, and how their oversight work could help inform disaster recovery policy in the future.

In full-day workshops we split the presentation portion into several parts (typically investigations, hearings, written products, and follow-up) and conclude each section with a group project centered around a simulated scandal – the closest anyone can get to state government fan fiction.

In a recent Pennsylvania workshop, participants planned an investigation, a hearing, and follow-up activities for a (completely fictional) state hospital system caught up in swirling accusations of ill-gotten contracts, patient deaths, and failing medical records. The exercise was a deep dive into legislative oversight, with all the nuances of overlapping issues, muddy agency jurisdictions, working across the aisle, and important questions like, “How should a committee handle whistleblowers?” and “What do you do with a high-level state employee who puts ‘tell the civil service guys to kick rocks’ in writing?” Of course, it all comes with plenty of feedback from instructors and peers.

That peer feedback gives participants a rare opportunity to work together in a low-stakes situation and to strengthen their connections – especially with their colleagues across the aisle. As much as anything else, SOA workshops are a chance for legislative professionals to collaborate with colleagues to develop their own oversight pursuits and to be inspired by the good they can do with their existing powers and resources.

The results speak for themselves. “I learned that there is an appetite for genuine oversight in Delaware,” wrote one participant who joined us on a December afternoon in Dover. Another recent participant wrote on their evaluation that “The exercises were terrific to actually walk through the process and gain a practical understanding.” At one regional conference of state government professionals, the State Oversight Academy’s oversight session was the most highly rated session by participants.

We share this not to boast, but because we would love to show you more, and we know good government requires oversight. If you’re interested in state legislative oversight (and if you’re not, what are you doing here?), we’ll visit your state and showcase through a workshop the power of collaborative oversight to enforce legislative authority on governmental performance monitoring. We’ll join your Zoom webinar. We’ll fly across the continent to present in a committee room with five people or the floor of a packed legislative chamber. We’ll speak to your oversight committee, caucus, staff retreat, new member orientation, or policy conference (and, while we haven’t been asked to do any weddings or bar mitzvahs yet, there’s a first for everything).

So, (and here comes the first sales pitch in the history of the SOA blog) we’d love you to get in touch. You can contact Ian McKnight (ianmcknight@wayne.edu) and Ben Eikey (benjamin.eikey@wayne.edu) to get started. Whether you’re looking for a lunch and learn, an all-out simulated scandal extravaganza, or an in-person workshop or a virtual event, we’ll put together an oversight program you and your participants will love – and that will make a positive impact on your state’s oversight work for years to come.

Juvenile Justice: An Investigation in Four Parts

This month at the State Oversight Academy, we are taking a closer look at oversight of juvenile justice issues. Like any circumstance when government cares for people in a vulnerable position, juvenile justice is an area where heightened attention to the performance and integrity of public programs makes sense. At the same time, shifting attitudes and policies around criminal justice and changing understandings of youth development have pushed juvenile justice into the oversight limelight in recent years.

This month’s Oversight Overview video examines legislative oversight of juvenile justice in Connecticut, New Jersey, and Kansas, as well as the resulting policy reforms. The oversight approaches detailed here illustrate how state legislators are using the power of their offices to pursue facts through university collaboration, expert commissions, and department reports.

Another state also recently zeroed in on juvenile justice: Kentucky. Following several incidents in juvenile detention centers, the state legislature has been working to find the facts and change their system for the better. Their work gives us an opportunity to examine an oversight investigation as it happens.

At the Levin Center, we think of an oversight investigation in four parts: the investigation itself, a written product, a hearing, and a program of follow-up. The investigation finds the facts; the written product lays them out; the hearing puts those facts on the record with witnesses and a measure of direct accountability; and the follow-up aims to translate elevated awareness of the problem into effective solutions. With that in mind, look at Kentucky’s juvenile justice work in the context of those four phases.

The Investigation

Kentucky’s Legislative Oversight and Investigations Committee (LOIC) is the main investigative committee for Kentucky’s legislative branch. Its members come from both the House and Senate, and its authorizing statute gives them broad powers to study state agencies and issue reports and recommendations.

In August of 2022, a teen in the Jefferson Regional Juvenile Detention Center near Louisville set a fire with a lighter she had smuggled in. For safety, other teens were let out of their rooms, and one of them scaled a fence and briefly escaped. On October 13, 2022, LOIC directed its staff to investigate the incident.

Less than a month later at a separate facility, a riot broke out after a teen stole keys from an employee and used them to unlock the cells of 32 others. The Associated Press reported that state troopers and other law enforcement had to be summoned to restore order, and reports of a sexual assault during the incident made headlines.

The incident once again raised the profile of the state’s juvenile justice system. By February of 2023, the General Assembly had passed a concurrent resolution to establish a legislative work group on the matter. Though it did most of its work behind closed doors, the work group did issue a number of recommendations some weeks later.

Meanwhile, much of LOIC’s investigative work was carried out by staff, who conducted interviews of everyone from Department of Juvenile Justice leadership to local fire officials, to department staff in other states. They visited juvenile detention centers in Kentucky and beyond and reviewed historical data from every corner of Kentucky’s juvenile justice system. By the summer, they had compiled their findings in a written report.

The Written Product

By July of 2023, a team of a dozen staff had produced a 171-page report detailing not only specific problems in the juvenile justice system, but the factors that had led to them. The report included information on facilities, staffing, transportation, administrative structures, legislative history, and much more. It examined changes in mental health among juvenile offenders and other states’ work to address them.

All told, the report included 30 recommendations ranging from increasing the online presence of the Department of Juvenile Justice’s ombudsman to improving the department’s system for recording gang affiliations. While some recommendations require legislation, most are operations reforms.

Hearings

Even before the report was finished, LOIC held a hearing in June during which leadership from the Justice and Public Safety Cabinet and the Department of Juvenile Justice gave updates in initiatives to fix staffing and security issues in the system, as well as updates on the implementation of related legislation. The same leaders returned for LOIC’s July meeting where they were asked to provide their response to the staff report.

In October, department leadership was called before LOIC once more to address issues around the use of pepper spray and isolation for offenders, actions in violation of the department’s own policies. The hearing received newspaper and television coverage, raising the profile of the issues.

Follow-Up and Policy Impact

Increased attention – by the legislative branch, the media, and the public – has already led to some reforms. During their session in winter of 2023, the General Assembly passed two appropriations bills to address staffing and facilities issues within the Department of Juvenile Justice, both of which were signed by the Governor at the same time as he ordered other reforms. While the reforms predated the report and many of the hearings by LOIC, they did come on the heels of a press conference by the legislative work group created shortly before.

In November 2023, the Governor announced the resignation of the Juvenile Justice Commissioner. The move came in the wake not only of work by LOIC, but also staff whistleblowers and mounting media coverage detailing bad conditions in juvenile detention facilities.

“I think we’ve got a good road map for DJJ.” The Governor said of the Department of Juvenile Justice in November. “I believe that if we continue to work the plan in coordination with the General Assembly, that we are already in a better place and we are getting to a better place.”The Governor’s 2024 budget proposal includes major funding for juvenile justice facility improvements. The General Assembly is in session through April 15.

Too often, the last oversight step – follow-up – falls by the wayside as the legislature is pulled in other directions. Continued oversight interest, movement toward reforms, and media headlines are encouraging signs that the legislature is committed to seeing the reforms through and ensuring that they are implemented and produce positive results.

Eyes, Voice, and Teeth: Subpoenas in State Legislatures

We already know what the Supreme Court says about oversight: “It is the proper duty of a representative body to look diligently into every affair of government and talk much about what it sees. It is meant to be the eyes and voice, and to embody the wisdom and will of its constituents.”

To be the eyes and voice, and to embody the wisdom and will is an enormous and challenging responsibility. It is one that requires the ability to collect vast amounts of information that is not always readily available, or whose keepers are not eager to share it. And, sometimes, the eyes and voice also need to be backed up with teeth. That is where subpoenas come in.

Typically issued by courts or legislatures, a subpoena gives the issuing authority the ability to compel the production of information in the form of documents or testimony. Although we often hear about Congress issuing subpoenas, most state legislatures have subpoena authority in some form or another. Even if they do not often exercise that authority, it offers two primary benefits:

Most obviously, subpoena authority provides an important means of compelling the production of information when an entity refuses to produce that information voluntarily. When the Supreme Court defined Congress’ power to issue subpoenas in McGrain v. Daugherty after the Teapot Dome scandal, they wrote:

“A legislative body cannot legislate wisely or effectively in the absence of information respecting the conditions which the legislation is intended to affect or change, and where the legislative body does not itself possess the requisite information — which not infrequently is true — recourse must be had to others who do possess it. Experience has taught that mere requests for such information often are unavailing, and also that information which is volunteered is not always accurate or complete, so some means of compulsion are essential to obtain what is needed.”

Even in instances when entities provide information to a legislature without the use of a subpoena, we may have the subpoena power to thank. This is because of the second benefit of subpoena authority: its softer power as an incentive to comply with an information request. The mere specter of a subpoena – the unspoken possibility that one may be issued – is often sufficient for securing the desired information.

In any case, the effectiveness of a subpoena also depends on an institution’s ability to enforce a subpoena. In general, subpoenas issued by Congress or state legislatures are not self-enforcing. Legislatures must seek enforcement of their subpoenas either by bringing a civil action in court or by voting to hold a non-respondent in criminal contempt of the legislature and referring the matter to the executive branch for possible criminal prosecution.

While most states legislatures have some form of subpoena power, the source of that power, the part of the legislature in which it is vested, and the mechanisms for its enforcement vary widely. The power can come from the state’s statutes, the rules of legislative chambers or, as is the case in Maryland, even from the state’s constitution itself. The ability to issue subpoenas may rest with a committee or multiple committees, or it may require authority from legislative leadership or a vote of another committee or even an entire chamber. (As ever, you can find specifics on your state in our fabulous State Legislative Oversight Wiki.)

In Michigan, the power to issue subpoenas is granted to committees by both statute and by the rules of the House and Senate. Any exercise of this power also requires an authorizing resolution from the relevant chamber. A person failing to comply with a subpoena from the Michigan Legislature may be held in contempt of the Legislature, a misdemeanor charge the penalties for which can include five years in state prison or a fine not to exceed $1,000.

The General Assembly in Connecticut has broad investigative powers authorized by statute. Not only legislative leadership, but any committee “shall have the power to compel the attendance and testimony of witnesses by subpoena and capias issued by any of them, require the production of any necessary books, papers, or other documents, and administer oaths to witnesses in any case under their examination.” The State’s Attorney in Hartford (a prosecutor role appointed by an executive branch commission) may prosecute witnesses who fail to testify.

The Oklahoma House of Representatives’ rules authorize its committees and subcommittees, among other things, to “invite public officials, public employees, and private individuals to appear before the committees or subcommittees to submit information.” If the invitation does not yield results, “the chairperson of each committee with approval of the Speaker, may issue subpoenas and other necessary process to compel the attendance of witnesses” or the production of documents.

This week, The Oklahoman reports, the House did just that. After the Superintendent of Public Instruction did not respond to invitations to provide information to the House Education Committee, the committee chair and Speaker issued a subpoena, an instrument which, The Oklahoman notes, “is rarely used by the Oklahoma Legislature.” The subpoena invokes Article 5, Section 42 of the Oklahoma Constitution, which authorizes either chamber of the Legislature to “punish as for contempt, disobedience of process, or contumacious or disorderly conduct.”

“Where taxpayer money is concerned, we must be diligent,” said the chair of the Education Appropriations and Budget Subcommittee, whose signature appears on the subpoena. “The time for playing political games is over, and the time for answers is at hand.”

While the nature of subpoena power varies by state, its value is the same. If its mere persuasive effect helps the legislative branch collect the information it needs, so much the better. But when the time for answers is at hand – when the eyes and voice need teeth to back them up – subpoena power is a critical tool for oversight.

SOA Symposium in Review

In November, the State Oversight Academy held its inaugural symposium – an all-virtual event dedicated to fostering meaningful conversations between scholars who study oversight and public servants who have dedicated their careers to it.

You can watch the full event on our website.

The symposium consisted of three panels. In each one, scholars who had submitted a working paper were paired with an oversight practitioner to provide comments on their work. The goal, as the State Oversight Academy’s Academic Director, Marjorie Sarbaugh-Thompson, put it, was to help “ground academic research in the realities of day-to-day governing and expand the options and perspectives of practitioners and academics in their work” – to bridge the gap between theory and practice.

Professors Seth Hill and Pamela Ban of the University of California San Diego presented their working paper, “Efficacy of Congressional Oversight,” which was reviewed by Joe Coletti, Oversight Staff Director at the North Carolina General Assembly.

Professor Dan Butler of Washington University of St. Louis presented a paper he coauthored with Professor Jeff Harden of the University of Notre Dame: “Can Institutional Reform Protect Election Certification?” It was reviewed by Kade Minchey, Auditor General for Utah’s Office of the Legislative Auditor General, whose office recently [IM1] [KG2] completed a performance audit of Utah’s election system just last year.

Finally, Professor James Strickland of Arizona State University presented his paper on conflicts of interest among the clients of multiclient lobbying firms: “Why Hospitals Hire Tobacco Lobbyists.” He received feedback from David Orentlicher, who serves in the Nevada House of Representatives, previously served in the Indiana House of Representatives, and holds both a JD and an MD. He is also a law professor at the University of Nevada Las Vegas.

The scholars who participated indicated that the symposium achieved its goal of making practical connections and broadening horizons. Said one, “The comments from our discussant were insightful and practical. He gave great direction on how to take our current project and make it something that would have a greater impact. It was a great experience, and we are really glad we did it!”

The State Oversight Academy focuses on making connections – connections between academics who study state oversight, connections between public servants across the country who do the work of oversight, and connections between scholarship and practice. The November symposium did just that.

Perhaps it is a cliché to suggest that “more research is needed” on an issue. When it comes to oversight in state government, though, it could not be truer. Most of the work of governance in the United States goes on not in the halls of Congress, but at the state level. At the same time, a disproportionate amount of academic attention is focused on Congress rather than on state governments, and on legislation rather than oversight.

The State Oversight Academy is here to change that, and this year’s symposium is just the start. If you are a scholar with an interest in government oversight at the state or local level, or if you are a practitioner looking to share your knowledge or sharpen your skills, let us know! Our team would be glad to hear from you, and you just might wind up in our 2024 Symposium.

To inquire about the 2024 Symposium, contact Kyle Goedert at kgoedert@wayne.edu.

Look Diligently into Every Affair: Ombuds in State Government

At the Levin Center, we often quote a description of legislative oversight that the Supreme Court borrowed from Woodrow Wilson: “It is the proper duty of a representative body to look diligently into every affair of government and to talk much about what it sees. It is meant to be the eyes and the voice, and to embody the wisdom and will of its constituents.”

It is a tall order to “look diligently into every affair of government.” That was true when Woodrow Wilson wrote those words in 1885, and it is even more true today. Society has grown more complex, and the affairs of government have grown with it. So, too, have the tools for oversight in state legislatures, such as expanded member staff and what we often call analytic bureaucracies or oversight partners.

Analytic bureaucracies and oversight partners are the people and institutions – typically non-partisan – that support legislative oversight. Auditors and inspectors general, fiscal offices, and comptrollers can all fall into this category. Often, they are housed in the legislative branch and their work relates to state government financial and broad operational concerns.. They are an important tool for the legislative branch to look into the affairs of government, conducting audits and drawing up the reports that are often used in committee hearings or other legislative activity. If you want to see the oversight partners in your state, you can find them in our State Legislative Oversight Wiki. They are a vital part of the legislative branch’s ability to collect and analyze information about government function.

At the other end of the oversight spectrum is constituent casework, the subject of last month’s State Oversight Matters post and the most end-user focused exercise of oversight power by legislators and their staff. Casework typically concerns the experience of an individual constituent dealing with a government agency, and it can be a valuable source of information on how public policy and its implementation works for the people it directly affects.

Between analytic bureaucracies that deal with auditing and analysis and the granular world of constituent casework is a very special kind of oversight partner: the ombudsman. The idea of an ombudsman (also called an ombudsperson or just an ombuds, though ombudsman is also widely accepted as a gender-neutral word) is a European innovation. The term came into its modern use when Sweden established the Riksdagens Ombudsmän – the Parliamentary Ombudsman – to “monitor the compliance of public authorities with the law” in 1809 (the same year, for context, that the Pennsylvania General Assembly created their Auditor General). Today, Sweden’s Parliamentary Ombudsman bills itself as “a pillar of constitutional protection for the basic freedoms and rights of individuals.”

Today, the term in the US is not limited to use in state legislatures. The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau has an ombudsman, and the State Department has one just to handle employee disputes. Detroit (the Levin Center’s hometown!) has an ombudsman appointed by the City Council to address citizen concerns, and so does Anchorage. Even National Public Radio had an ombudsman until they changed the title in 2019.

For our purposes at the State Oversight Academy, though, we are primarily concerned with ombudsmen who are part of the legislative branch of state government. For the most part, these offices made their jump across the Atlantic from Sweden and into state legislatures around the mid-to-late twentieth century. Like the Swedish Parliamentary Ombudsman, they are primarily concerned with ensuring that public authorities comply with the law and protect the rights of individuals.

Ombudsmen exist in a middle ground of oversight resources between a caseworker and an auditor, and they are a particularly interesting, very special legislative resource. While caseworkers are often concerned strictly with individuals and auditors usually work with performance evaluation, ombudsmen are typically empowered to address both the concerns of individuals and larger systemic issues. Often, they bring to the table a level of specialized institutional knowledge that can help bridge that gap between legislators and agency staff and cut through red tape.

Today, we will look at three legislative Ombudsmen, in Hawaii, Iowa, and Michigan. Hawaii and Iowa have ombudsmen with broad authority to address public complaints about state government. Michigan has several ombudsmen with specific jurisdictions. We will specifically examine their Legislative Corrections Ombudsman.

Hawaii

The Hawaii Office of the Ombudsman was established in 1969. It identifies as a “classical ombudsman” with broad investigative authority over much of state and county government, but no enforcement power. The Office’s fiftieth annual report explained the Ombudsman as “an independent, non-partisan, and quasi-adjudicative officer of the legislative branch of government.” It also asserted that the office’s investigative role is “an extension of the power of legislative oversight.”

The Hawaii Office of the Ombudsman accepts complaints about state and county agencies from the general public. An annual report for the 2021-2022 fiscal year shows that the office receives more than 4,000 complaints within its jurisdiction each year. More than half of those complaints concern the state’s correctional system. Investigations included everything from missed bulk trash collection in an apartment complex to a data entry error extending an inmate’s prison release date. All of the office’s selected investigation summaries share a common thread: they are systemic problems that require significant investigative work and institutional knowledge, but they also have immediate, pressing consequences for individuals. They are uniquely suited to the role of the ombudsman.

Iowa

Like Hawaii, Iowa has a “classical” ombudsman located within the legislative branch with broad investigative authority over both state and local governments. Alaska, Arizona, and Nebraska are the other three states to have such a structure, though these offices only have oversight authority over state government. Worth mentioning, the Nebraska Ombudsman has recently been ensnared in legal questions from the Attorney General about the authority of the state’s Inspectors General, which it houses.

In another similarity to Hawaii, roughly half of the complaints that the Iowa Office of Ombudsman received last year concerned state prisons or county jails, according to its annual report. That same annual report contains a great variety of other complaints and investigations, ranging from drugs in prisons to unemployment insurance complaints.

The number and breadth of these investigations again reveals that the Iowa Office of Ombudsman serves not just as an important oversight mechanism for the legislative branch in which it is housed, but an important resource for Iowans. It is a direct connection between individual service and broader oversight function.

Michigan

Michigan does not have a single, unified ombudsman’s office in the style of Hawaii or Iowa. Instead, the Legislature has created a number of unique ombudsmen who deal with specific areas in state government. The Legislative Corrections Ombudsman, created by the Legislature as a part of the legislative branch in 1975, investigates complaints regarding the State’s prison system. By law, the LCO has unrestricted access to the Department of Corrections’ facilities and documents. The LCO’s website states that its goal is to “attempt to resolve complaints, when substantiated, at the lowest level possible within [the Department of Corrections], identify and recommend corrective action for systemic issues, and keep the Legislature informed of relevant issues regarding Michigan’s corrections system.”

Unlike the Ombudsman offices in Hawaii and Iowa, the Michigan Legislative Corrections Ombudsman accepts complaints only from prisoners and their families, prison staff, and legislators. While this is more restrictive than the rules of engagement for ombudsman offices with wider jurisdictions, it also centers the role of lawmakers, making Michigan’s Legislative Corrections Ombudsman an even clearer mechanism of legislative oversight. In a state with legislative term limits, the LCO also gives the Legislature a more equal footing in terms of continuity and institutional knowledge in its engagement with the Department of Corrections and its complexities.

The specialized Legislative Corrections Ombudsman in Michigan and the volume of corrections-related complaints to ombudsmen in other jurisdictions speaks to the importance of ombudsmen in corrections roles and more broadly. For people involved with the corrections system, an ombudsman is a rare neutral third party who can help mediate disputes, handle individual concerns, and address broader institutional issues. For legislators, an ombudsman can help bridge the gap between legislation and implementation and fill the gaps in institutional knowledge that are a natural side effect of electoral turnover. In Michigan, legislators found the Corrections Ombudsman structure to be valuable enough that they created a similar Veterans’ Facility Ombudsman in 2016.

Ombudsmen are rarer in state governments than more traditional analytic bureaucracies, but they are a valuable oversight tool. They connect people to their government, provide a neutral party for dispute resolution, and help to correct broader institutional issues. Most important of all, they are a vital mechanism to do some of the most important work of the legislative branch: to look into every affair of government and to talk much about what they see.

Reframing Casework as Oversight: Theory and Practice

When they picture oversight, most people might imagine a hearing room with Oppenheimer-esque drama unfolding or a group of accountants with green visors and Dixon Ticonderoga #2 pencils poring over financial statements. Those are important parts of oversight (though most C-SPAN content never makes it to IMAX and most accountants prefer Excel), but oversight at its best is more holistic. In fact, good oversight belongs in every part of legislative work. This is particularly true in the world of casework and constituent service which, when it is done right, can be a critical part of any oversight operation.

Constituent casework is a familiar concept for anyone in a legislative office. It is a simple idea: a constituent contacts their elected official to get help with some government function and the elected official helps them resolve it – usually in tandem with a contact within the department in question. The scope of casework is as wide as the scope of government itself – at the state level, it can involve anything from pothole repair to tax questions to health insurance appeals. Casework is about as old as our system of government, too. Work from the Congressional Research Service points to diary entries from John Quincy Adams during his time in Congress, who noted that he assisted constituents with a date correction on a military pension certificate, as well as appointments to certain government positions. Representative James A. Garfield, later to become the president, intervened in the case of lost mail and a delayed patent extension (Petersen and Eckman 2021).

Casework is an important part of the American legislative tradition and a familiar fixture of almost any office, but what is the point? The easy answer is that it is good politics, and that is not wrong. A track record of small bureaucratic victories for constituents can have a “substantial effect” (Yiannakis 1981) in electoral performance, but it would be cynical to suggest that casework is only a thinly veiled campaign strategy. Done right, casework is more than just a political tactic or an intern task; it is a critical exercise of oversight powers.

Casework cuts to the most important question we can ask in oversight: beyond simple adherence to policies and procedures, is government delivering on its promises to people?

This question – the one of actual service delivery – is important in any large operation. It is the same reason we all receive an astonishing number of interminable emailed surveys every day asking whether we would recommend our electric toothbrush to a friend or colleague, if the airplane flight attendant smiled with sufficient enthusiasm at the end of our flight, or how satisfied we were with the cleanliness of our apartment building’s stairwell during the month of April.

In government, though, those questions are even more important. With all due respect to the enthusiastically smiling flight attendant, the stakes are higher when it comes to delivering timely health benefits or caring for vulnerable people. The benefit of a legislative environment is that legislators and staff are in a unique position to learn whether government delivers on its promises – even without a survey. After a few years in office, their phone number or email address has worked its way onto fridge magnets, sticky notes, and Facebook groups in every corner of the district. The consequence of this is that when unemployment checks do not arrive, potholes appear on the expressway, or the Tax Department sends out an even more cryptic and threatening mass mailing than usual, they hear about it.

Casework is always a challenge, even at its most basic transactional level. The special challenge in getting it right, though, is treating it like the valuable oversight mechanism that it is. In that spirit, here are a few tips for legislative offices looking to do just that.

- Collect data and use it wisely. It is possible to run a casework program on sticky notes, but it is not advisable. By developing a good system and collecting standardized data about each case – the basics of the problem, how it is resolved, where the constituent lives, and so on – it is possible to find new insights that are helpful both for constituent service and for larger oversight operations. Do people who live near a particular DMV office have a higher chance of delays in renewing their driver licenses? Do you always hear more about unemployment insurance problems in the fall after agricultural workers lose seasonal work? Is there a more effective way to handle a process than the one an agency publicizes on their website? Good data collection and analysis are easier than they sound and can help answer these questions.

- Casework is for everyone. It can be tempting to think that constituent service is a task for interns and newer staff, a bad habit that is often perpetuated by staff hierarchies. That does not mean that moving on to a policy position is a license for a staffer to cut their phone cord or disengage with casework data, or for a legislator to treat casework as staff busywork. Casework, oversight, and legislation are all closely related. Oversight and legislation benefit enormously from people who have first-hand experience interacting with the systems being overseen or regulated.

- Keep good records on people and keep those people in mind for other projects later. Constituents call legislative offices because they care, they want to have their story heard, and they want systems to work better for themselves and others. It helps to make a note when a constituent has a unique case or a compelling story. They can make a great case study or even a witness at a hearing if their story is relevant for a broader oversight project or for legislation. They will often be glad to be included in the process.

Every legislative office has done constituent casework in one way or another, but it takes real work – a complete reframing, even – to realize the full potential of casework. Used as an oversight tool, casework embodies the very best of good government in a democracy. It transcends the noise and complexity of minute details to ask the single, persistent question at the core of all oversight: Is our government delivering on its promises to people, and how can we do it better?

References

Petersen, R. Eric, and Sarah J. Eckman. 2021. Casework in a Congressional Office: Background, Rules, Laws, and Resources. Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/RL/RL33209/29.

Yiannakis, Diana Evans. 1981. “The Grateful Electorate: Casework and Congressional Elections.” American Journal of Political Science 25(3): 568–80.

Interim Oversight

The end of summer is, in general, a quiet period for the nation’s state legislatures. Today, at the end of August, legislatures in more than half of the states have adjourned until next year unless a special session is called. Even in full-time institutions, schedules have slowed as legislators spend more time in their districts. From the Congress’ summer in-district work period to the long state legislative interim – the time when a part-time legislature is not in session – summer months without the rigors of regular session and committee schedules have long been a part of the American legislative tradition. They date back to a time when a substantial proportion of legislators had agricultural responsibilities, and before modern infrastructure cut down on travel time to state capitals.

A lot has changed since then. Society has become more complex, and governing has grown with it. Typically, the legislature hands off much of the work of implementing policy to the executive branch – the agencies and departments that build infrastructure, regulate industry, look after the vulnerable, and much more. Their responsibility for implementing the legislative branch’s policy never stops. At the same time, the legislature has a special, year-round responsibility to make sure the executive branch faithfully implements the law and to assess the efficacy of the underlying policy. That is oversight. Oversight is a unique right and duty for the legislative branch as a coequal branch of government – one that goes on all year.

A quieter schedule can give legislators and staff time to work on more involved and proactive oversight projects. Those projects, in turn, can set the stage for broader legislative fixes or budgetary tweaks when the full legislature comes back into session. Oversight topics needing a more comprehensive review can include child welfare services, prison operations, and infrastructure priorities. Conducting oversight on topics like these during the interim helps state legislators keep an eye on performance and prepare for an upcoming session when schedules tighten. In the world of oversight, the interim can be just as important as the height of a legislative session.

Every legislative institution has its own way of handling oversight during the interim. The Levin Center’s most recent Oversight Overview video explores the particulars of interim oversight committees working with child welfare in Alabama, Colorado, and Utah. In all three states, several specialized legislative interim oversight committees track a variety of issues, from nuclear energy to administrative rule review.

In West Virginia, where the Legislature’s regular session lasts only from January to March, a robust system of interim committees conducts most of the state’s oversight work during the rest of the year. While certain committees focus on a specific issue area such as education or transportation, a joint Commission on Special Investigations has broad authority and a full investigative staff. All interim committees have a mandate to return a report with their findings to the whole Legislature. The effect of this is that, while the House and Senate may be out of session, the legislature still plays its part as a coequal branch of government all year. While West Virginia’s regular session ended in March, legislators there have continued studying issues like corrections staffing and delays in issuing death certificates.

In Louisiana, standing committees – not just those focused specifically on oversight – have broad authority to conduct most of their oversight operations during the interim. They can establish subcommittees, hold hearings, review proposed administrative rules, conduct investigations, and more. At the same time, the Legislative Audit Advisory Council uses its time in the interim to review reports from the state legislative auditor, as they did in July at a hearing concerning the Governor’s Office of Elderly Affairs. Aside from just freeing up committee time during the busy session, handling this oversight work during the interim ensures that legislators and staff have the time they need to conduct detailed investigations and prepare thoughtful policy in response. Their system contributes to meaningful, year-round oversight and helps the Legislature hit the ground running during their two-month regular session.

Even though it may seem like a quiet time of year in terms of legislation, good oversight work never stops. Across America, committees keep meeting, auditors keep auditing, and investigators keep investigating. It has been a busy summer at the Levin Center, too. Our State Legislative Oversight Wiki has been revamped with version 2.0, with more information than ever. It is a great tool to learn about oversight operations across the country, and you can even provide updates about how your state’s legislative institutions keep busy with oversight during the summer.

State Legislative Oversight Wiki 2.0 is here!

Today, the State Oversight Academy is excited to launch a brand-new version of the State Legislative Oversight Wiki. Wiki 2.0 includes added information on committees with jurisdictional oversight authority, as well as agency reports by topic from across the United States. The fresh interface is easier to navigate and allows researchers, legislative staff, and the public to search by topic, keyword, and state.

Whether you are a researcher looking for committees with jurisdictional oversight authority in Guam or a legislator searching for reports on corrections from across the nation, you will find it – and a whole lot more – on Wiki 2.0.

For every state, territory, and the District of Columbia, Wiki 2.0 includes basic information on the structure of the legislative branch and on committees with oversight and fiscal authority, as well as details on oversight partners like auditors and inspectors general, ombudsmen, and research agencies. A separate section for agencies and reports displays agencies by function (such as auditors and comptrollers), as well reports by subject area (e.g., elections and social services).

With a new keyword search tool, everything is easier to find in Wiki 2.0. A dropdown menu makes it possible to search for resources in just one state or across the country. Using “quotation marks” allows for narrowing a search to a precise phrase. For example, searching House Fiscal Agency would display any result including House or Fiscal or Agency, but searching “House Fiscal Agency” displays only Michigan’s House Fiscal Agency.

Sharing a direct link to a section is easier in SOWIKI 2.0. Click the hash mark (#) next to any section header to copy a direct link to some featured reports from the Louisiana Office of the Inspector General or general information on Florida’s term limits.

Most important of all, Wiki 2.0 is a collaborative effort. You (yes, you!) can help us keep the State Legislative Oversight Wiki up-to-date and share your ideas for improvement. On every page you will find an area to send updates or just share your thoughts. You can also use the green chat button in the lower right-hand corner to send questions or comments. We are excited to hear from you!

Wiki 2.0 is just the State Oversight Academy’s latest tool to compile detailed information about oversight across the country in one unified resource. Building on the Levin Center for Oversight and Democracy’s comprehensive 2019 study on oversight across the states, the Wiki’s flexible format and the ability for anyone to submit updates will help keep information on the dynamic world of legislative oversight up-to-date and make it a useful tool for years to come.

Visit Wiki 2.0 here now!

Prison Operations Oversight: How Two States Find Facts on What Happens Inside Prison Walls

State legislatures across the country use their fiscal and policy-making leverage to conduct oversight on state prison operations. Unlike the rules governing other areas of state government, state corrections law often grants prison officials a significant degree of discretion to decide what happens and what is funded inside prison walls. To keep track of these highly variable operations, state legislatures have adopted a number of practices, including requiring agency reports, forming joint legislative committees to conduct oversight, and establishing expert commissions to gather and review data about prison performance.

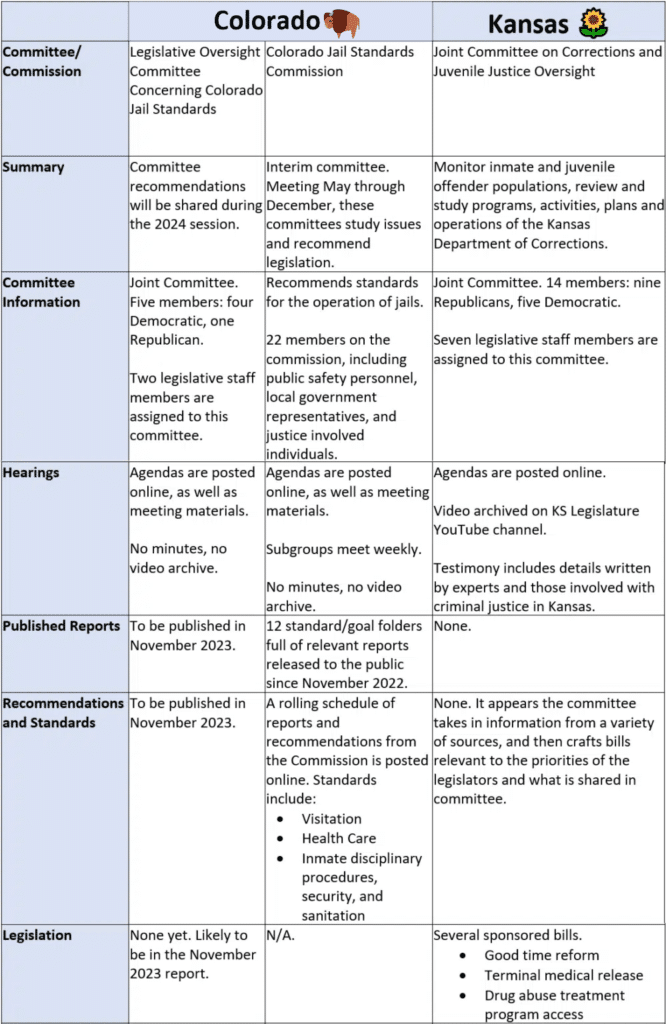

Some legislative committees implement recommendations developed by an appointed commission of professionals, while others operate independently as a committee or member office. This blog explores the joint legislative committees on prison operations in Colorado and Kansas.

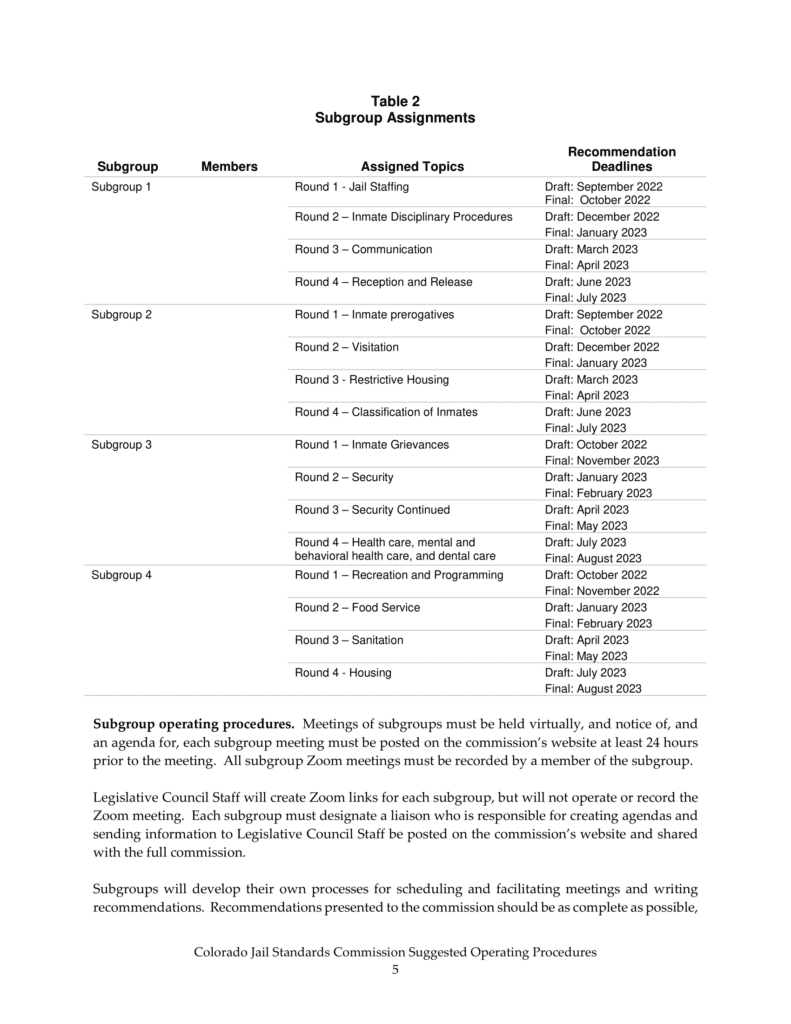

This table reflects the information available on the committee or commission websites or hearing recordings on YouTube from the state legislature.

Links:

- Legislative Oversight Committee Concerning Colorado Jail Standards

- Colorado Jail Standards Commission

- Kansas Joint Committee on Corrections and Juvenile Justice Oversight

Colorado: Colorado’s commission appears to be stocked with experts. The commission’s adopted topics and the corresponding deadline for recommendations appears to be an effective planning framework. The commission releases recommendations on topics such as jail staffing, security, and visitation every three months. The last crop of commission recommendations is scheduled for August 2023 followed by the full committee report in November. These topics could inspire other state legislatures to pursue investigations in their own state, or even adopt Colorado’s ambitious timeline approach for topics and recommendation delivery. The commission’s operating procedures are listed below.

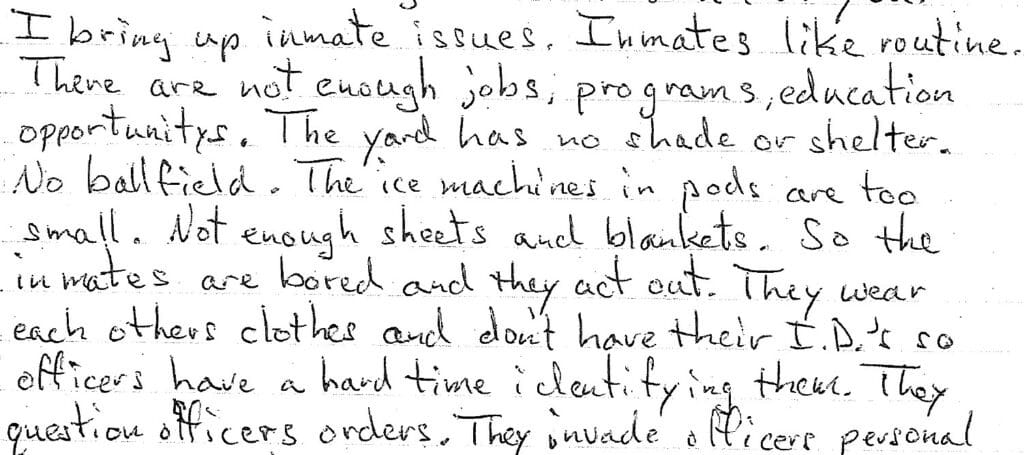

Kansas: The committee heard testimony from citizens and experts representing interest groups. The committee record also suggests that the committee heard from a wide range of viewpoints. For example, reproduced below is an excerpt from the written testimony from a Kansas resident in which he shares concerns about prison operations after working as a corrections officer for 20 years. Personal letters like this are in included in the record along with issue statements from interest groups.

Based on this review, it’s clear that lawmakers in Colorado and Kansas take seriously the job of tracking prison operations within their jurisdictions. Each state might benefit from considering the practices of the other. Kansas, for example, might want to form a commission on prison operations or make a topics timeline to plan out the fact-finding within their own committee. Colorado might consider seeking more public and interest group input on the committee’s operations, recording commission and committee meetings and uploading those recordings to YouTube, and holding committee hearings every few months to share and discuss the recommendations developed by the commission. Any state legislature should consider combining Colorado’s expert recommendations and planning with the hearing and testimony structure from Kansas when preparing to conduct oversight on state prison operations.

The Levin Center’s State Oversight Academy exists to help state legislatures working to conduct fact-finding. From prison operations to monitoring implementation of any government program, the Levin Center supports legislatures in fulfilling their duty to serve as the “eyes and voice of the people.” If you enjoyed this blog, please consider subscribing to the State Oversight Academy newsletter at https://www.levin-center.org/state-oversight-academy/. If you are a state legislator, consider attending the Levin Center’s upcoming virtual MasterClass. State legislators from across the country join oversight experts to build a response to a hypothetical prison operations scandal. Link to RSVP: https://www.levin-center.org/event/oversight-of-prison-operations-an-interactive-masterclass/.

For questions or comments, message Ben Eikey at benjamin.eikey@wayne.edu.