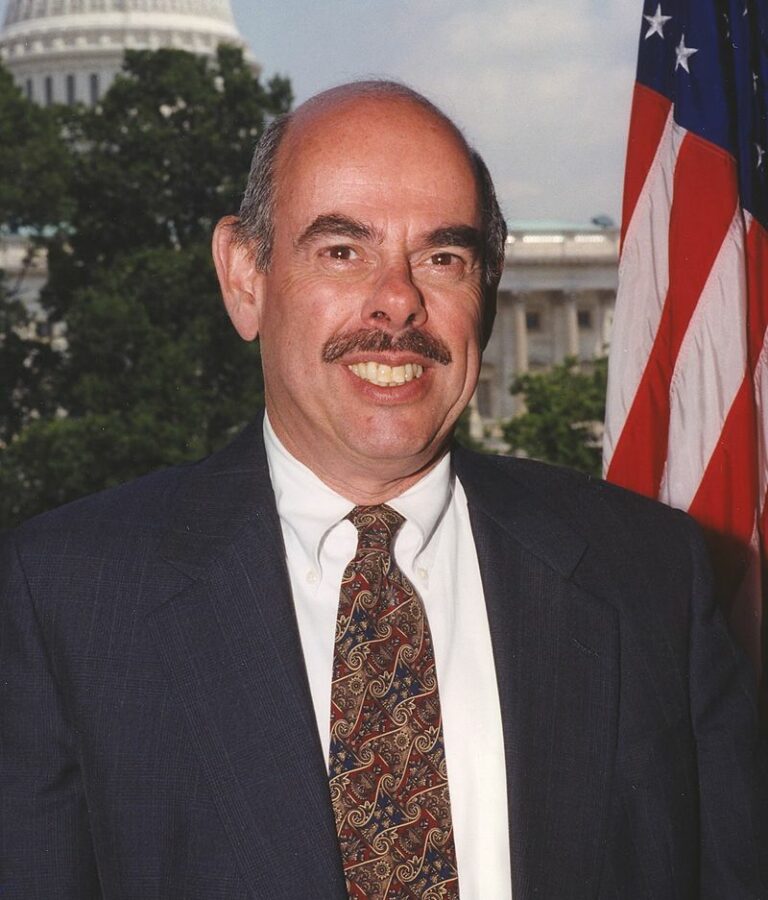

Portraits in Oversight:

Henry Waxman and Big Tobacco

Rep. Henry Waxman, a Democratic representative from California, used congressional oversight to wage a 25-year effort, from 1982 to 2009, to expose and mandate safeguards against the health hazards caused by tobacco products. His oversight hearings educated the public about the scientific evidence on tobacco’s dangers, disclosed industry actions to hide or downplay tobacco’s addictive and carcinogenic properties, and spurred multiple legislative reforms. His sustained oversight effort helped save millions of Americans from tobacco-related disease and disability as well as billions in taxpayer dollars that would have otherwise been spent on health care costs.

The first scientific evidence that smoking caused cancer in rats was published in 1953. The following year, the British Medical Journal linked it to lung cancer, heart disease, and other serious health problems. In 1964, the U.S. Surgeon General published a seminal report, Smoking and Health: Report of the Advisory Committee to the Surgeon General of the Public Health Service, confirming causal links between smoking and cancer. In 1966, Congress enacted legislation requiring that cigarette packs carry the health warning: “Caution – cigarette smoking may be hazardous to your health.”[1]

Despite the dire research and health warnings, millions of Americans – around a third of adults in the 1960s and 1970s – continued to light up, and deaths attributed to smoking remained high with 390,000 smoking-related deaths recorded in 1985 alone.[2]

In 1979, Rep. Waxman became chair of the House Committee on Energy and Commerce’s Subcommittee on Health and the Environment. As chair of the subcommittee, and later as chair or ranking member of the House Oversight Committee and then of the full Energy and Commerce Committee, he spent the next 35 years conducting oversight on a wide range of issues. In 1982, he held the first congressional hearing on the health risks of smoking.

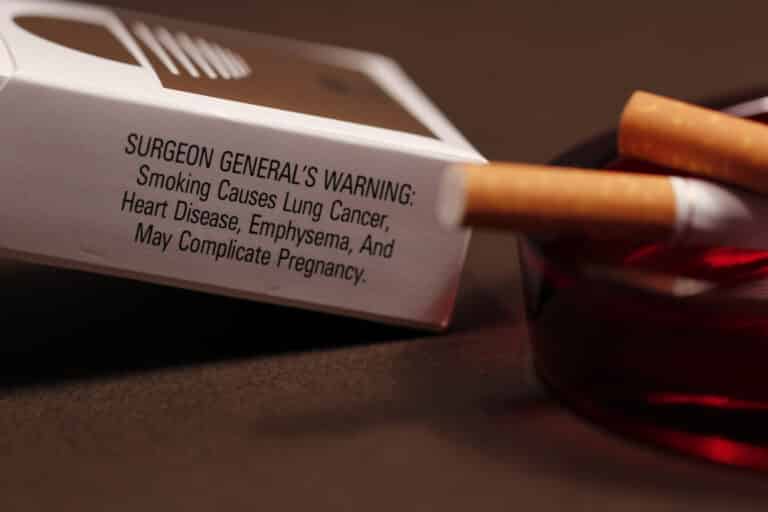

Following additional hearings, in 1984, Rep. Waxman won enactment of the Comprehensive Smoking Education Act which passed with a bipartisan group of 59 cosponsors. The law directed “the Secretary of Health and Human Services to inform the public of the health hazards of cigarettes through research, demonstration, and educational activities,” and required that cigarette packages and advertising carry one of the following warnings, which rotated quarterly:

- “SURGEON GENERAL’S WARNING: Smoking Causes Lung Cancer, Heart Disease, Emphysema, and May Complicate Pregnancy.

- “SURGEON GENERAL’S WARNING: Smoking by Pregnant Women May Result in Fetal Injury, Premature Birth, and Low Birth Weight.

- “SURGEON GENERAL’S WARNING: Cigarette Smoke Contains Carbon Monoxide.

- “SURGEON GENERAL’S WARNING: Quitting Smoking Now Greatly Reduces Serious Risks to Your Health.”

In 1985, Rep. Waxman held a hearing on the health effects of smokeless tobacco products such as snuff and chewing tobacco. The hearing examined evidence that the products caused a variety of oral diseases including premature tooth loss, precancerous lesions, and squamous cell carcinoma. As Rep. Waxman explained in his opening statement: “Smokeless tobacco is not, as its advertising suggests, a safe alternative to cigarettes.”[3] In 1986, Congress enacted the Comprehensive Smokeless Tobacco Education Act, championed by Rep. Waxman and Republican Sen. Richard Lugar of Indiana with a bipartisan group of cosponsors, requiring health warnings on smokeless tobacco products and banning advertisements on radio and television.

Around the same time, secondary smoke hazards began to attract attention. Surgeon General C. Everett Koop published a 1986 report entitled, The Health Consequences of Involuntary Smoking, in which he stated, “it is now clear that disease risk due to inhalation of tobacco smoke is not solely limited to the individual who is smoking, but can also extend to those individuals who inhale tobacco smoke in room air.”[4] In 1987, Congress amended the Federal Aviation Act of 1958 to ban smoking on flights less than two hours long, and in 1990, over intense opposition by the tobacco industry, prohibited smoking on all domestic flights. Then Rep. Dick Durbin of Illinois, whose father died of lung cancer, and Sen. Frank Lautenberg of New Jersey, led the efforts to pass both laws. In December 1992, the Environmental Protection Agency released its risk assessment, Respiratory Health Effects of Passive Smoking: Lung Cancer and Other Disorders, which classified secondhand smoke as a “Class A” carcinogen. In 1993, a Waxman subcommittee hearing detailed the damaging health effects caused by “environmental tobacco smoke.”

Interest in other types of tobacco-related research also increased. A February 1993 media exposé zeroed in on the Council for Tobacco Research, a group founded in 1958, and funded by the tobacco industry with the promise to conduct independent, scientific studies. The media disclosed that the council:

[H]as been the hub of a massive effort to cast doubt on the links between smoking and disease. … [L]ong run behind the scenes by tobacco-industry lawyers, the ostensibly independent council has spent millions of dollars advancing sympathetic science. At the same time, it has sometimes disregarded, or even cut off, studies of its own that implicated smoking as a health hazard.[5]

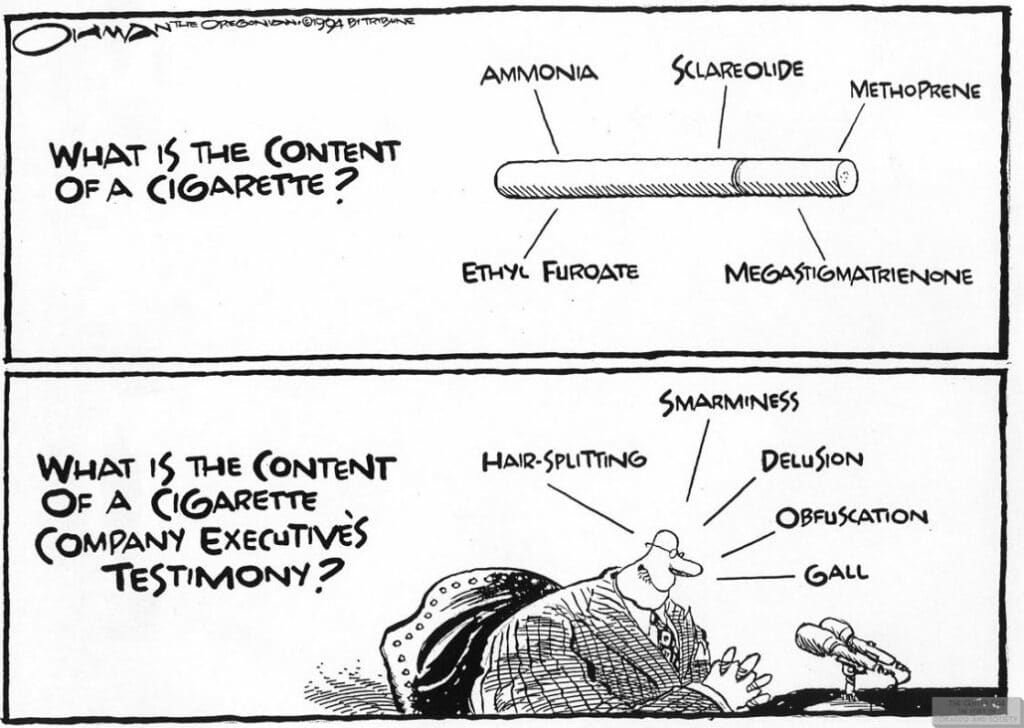

In February 1994, FDA Commissioner David Kessler announced evidence that tobacco manufacturers were deliberately manipulating the nicotine content in cigarettes and, as a result, the FDA was prepared to consider regulating tobacco products, a major policy shift. Three days later, broadcast network ABC aired a segment on its news show “Day One” asserting that tobacco companies were spiking nicotine levels to make their products more addictive.[6] Tobacco industry representatives denied it. “I don’t know what they could possibly be talking about,” said a spokesperson for the Tobacco Institute.

On March 25, 1994, the Waxman subcommittee invited FDA Commissioner Kessler to testify at a hearing about nicotine levels and the need for regulation. Commissioner Kessler provided dramatic testimony, describing cigarettes as “high-technology nicotine delivery systems” and detailing ways in which tobacco companies had manipulated their products to increase addiction. He testified, for example, that manufacturers poked tiny holes in cigarette filters, which would be covered by a smoker’s fingers or lips during use to increase the amount of smoke inhaled, but made the tar content appear lower on government monitors measuring it. The FDA also disclosed an R.J. Reynolds patent to more than double nicotine levels in its tobacco blends.

Following the March hearing, Rep. Waxman publicly announced that the subcommittee would invite the CEOs of America’s seven largest tobacco companies to appear at the next hearing and respond. He indicated that the CEOs would be the only witnesses called, and their chairs would stand empty if they did not appear.[7] The hearing caught the attention of the media and the public and became not only a notable event in congressional oversight history, but also a highpoint in the Waxman effort, now over a decade old, to force Big Tobacco to publicly admit tobacco’s health hazards.

On April 14, 1994, all seven tobacco executives appeared before the subcommittee:

- William Campbell, President and CEO of Philip Morris;

- Edward A. Horrigan, Chair and CEO of Liggett Group, Inc.;

- Donald S. Johnston, President and CEO of American Tobacco Company;

- James W. Johnston, Chair and CEO of R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company;

- Thomas E. Sandefur, Chair and CEO of Brown & Williamson Tobacco Corporation;

- Joseph Taddeo, President of U.S. Tobacco Company; and

- Andrew H. Tisch, Chair and CEO of Lorillard Tobacco Company.

In his opening statement at the hearing, Rep. Waxman said:

The truth is that cigarettes are the single most dangerous consumer product ever sold. Nearly a half million Americans die every year as a result of tobacco. This is an astounding, almost incomprehensible statistic. Imagine our Nation’s outrage if two fully loaded jumbo jets crashed each day, killing all aboard. Yet that’s the same number of Americans that cigarettes kill every 24 hours.[8]

The hearing itself lasted seven hours. During it, the tobacco executives testified, under oath, that they did not believe nicotine was addictive. They also denied using advertising that targeted children, despite ads featuring cartoon characters like Joe Camel or celebrity endorsements by movie stars.[9] They disagreed with the U.S. Surgeon General and American Medical Association estimates that more than 400,000 Americans died from smoking-related illnesses every year.[10] However, all admitted that they would prefer their children did not smoke.

In the days leading up to the hearing, Rep. Waxman released a 1983 paper by a former Philip Morris researcher, Dr. Victor DeNoble, describing animal studies that demonstrated the addictiveness of nicotine. At the hearing, Rep. Mike Synar, a Democrat from Oklahoma, questioned Philip Morris CEO Campbell about whether his company had refused to allow Dr. DeNoble to publish his research. When Mr. Campbell admitted that it had, Rep. Synar pressed him to release the researcher from a binding non-disclosure agreement so that he could testify before the subcommittee. After some back-and-forth, Mr. Campbell agreed. The other six executives then reluctantly agreed to share their internal research with the subcommittee as well.[11]

Not every subcommittee member supported the negative portrayal of tobacco and smoking. Republican Reps. Thomas Bliley of Virginia and Alex McMillan of North Carolina both represented districts with large tobacco-related farm economies. At the April 14th hearing, Rep. Bliley, whose district included Philip Morris’ main manufacturing facility, said in his opening statement:

I am proud to represent thousands of honest, hard working men and women who earn their livelihood producing this legal product. I am proud of all their positive contributions to my community, and I’ll be damned if they are to be sacrificed on the alt[a]r of political correctness. This Congress must not turn its back on science and reason just because of the bubble of popularity.[12]

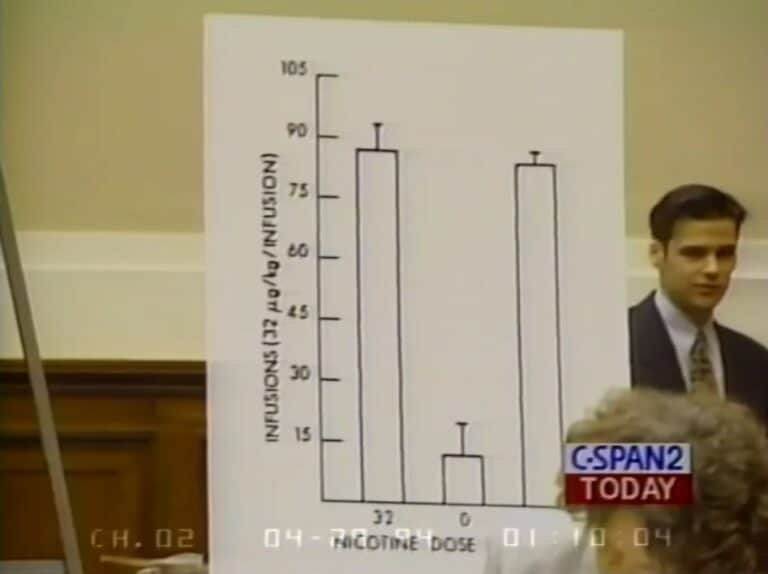

At a subcommittee hearing two weeks later on April 28, 1994, having been released from their non-disclosure agreements, Dr. DeNoble and his research partner, Dr. Paul Mele, testified about their tobacco-related research conducted during the 1980s. They contradicted statements made by the tobacco CEOs, for example, that nicotine was kept in tobacco simply for the flavor rather than for its addictive impact.[13] They showed evidence from their experiments that when rats were taught to press a lever to receive an injection of nicotine, they increasingly did so, demonstrating not only addictive behavior, but also how users build up nicotine tolerance over time.[14]

A few days after the hearing, the subcommittee obtained documents from a public relations firm retained by the tobacco industry’s trade association to combat anti-tobacco criticism and legislation. According to Rep. Waxman, some of those documents proved that “the industry had known for decades that tobacco caused cancer and had embarked on an elaborate disinformation campaign rather than come forward with the truth.”[15] The subcommittee released the documents to the public.

The following week, Mississippi’s attorney general Mike Moore, who was in the midst of a class action lawsuit against the tobacco industry, shared with the subcommittee additional internal documents from Brown & Williamson Tobacco Corporation. They had been provided by Merrell Williams, a law firm paralegal who formerly had access to company documents. Among other materials, Mr. Moore turned over a 1963 memorandum by the company’s general counsel stating that Brown & Williamson was “selling nicotine, an addictive drug.”[16]

Because the documents contradicted testimony given the prior month by Brown & Williamson CEO Thomas Sandefur, the subcommittee scheduled a hearing to recall him. On May 17, 1994, Brown & Williamson served subpoenas on Rep. Waxman and subcommittee member Rep. Ron Wyden of Oregon in connection with a lawsuit it had filed in Kentucky state court against Merrell Williams for stealing company documents. Brown & Williamson directed the two Representatives to produce the documents provided by Mr. Williams and planned to depose them under oath about the document theft.[17] Reps. Waxman and Wyden challenged the subpoenas in federal court, invoking the Constitution’s Speech and Debate Clause which protects Members of Congress from being questioned about their legislative actions. The district court quashed both subpoenas, an action later affirmed by the D.C. Circuit Court.

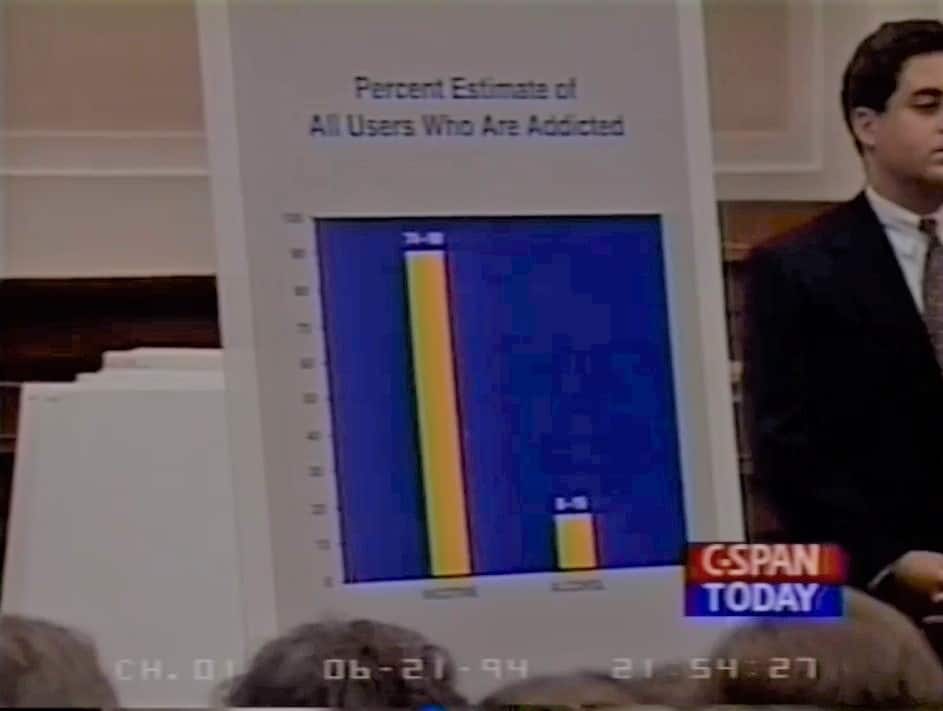

On June 21, 1994, the Waxman subcommittee reconvened once more and called FDA Commissioner Kessler to testify about tobacco’s addictive properties. He explained that while 8 – 15% of alcohol users become addicted, 74 – 90% of smokers do. When challenged by Rep. McMillan about whether cigarettes belong under the “addiction” umbrella with illegal drugs, Commissioner Kessler responded, “our focus, and the focus I think of this committee is not the fact that cigarettes are simply addictive, the problem is that cigarettes are addictive and they kill people.”[18]

Two days later, CEO Sandefur returned to testify before the subcommittee. Notwithstanding the 1963 company memorandum and other documents and research studies, he repeated his belief that nicotine was not addictive “based on my common sense understanding of the major difference between tobacco and drugs in terms of the way people behave and how many people have been able to quit smoking.”[19]

In 1995, Republicans won control of the House, and Rep. Waxman lost his position as subcommittee chair as well as his ability to call hearings. Nevertheless, he continued to receive internal documents from tobacco company insiders. On July 25, 1995, Rep. Waxman gave a speech on the floor of the House of Representatives under the protection of the Speech and Debate Clause. He used that speech to describe and read into the Congressional Record numerous tobacco company documents. One Philip Morris document, for example, entitled Relationship Between Smoking and Personality, described studies the tobacco company had begun to conduct on children:

Some children are so active (or “hyperkinetic”) that they are unable to sit quietly in school and concentrate on what is being taught .… Many children are therefore regularly administered amphetamines throughout grade school years. The wisdom of such prescription is open to question, and some published reports have suggested that caffeine in the form of coffee or tea for breakfast, would produce the same end result. We wonder whether such children may not eventually become cigarette smokers in their teenage years as they discover the advantage of self-stimulation via nicotine. We have already collaborated with a local school system in identifying some such children presently in third grade.[20]

Over time, still more tobacco industry whistleblowers stepped forward, including Brown & Williamson’s former vice president of research and development Jeffrey Wigand. His interview with 60 Minutes, which aired in 1996, exposed additional industry misconduct as well as company attempts to discredit him. The program was widely viewed by the public.

In 1997, Mississippi attorney general Moore announced that 40 states had reached a tentative settlement in their class action lawsuit against the tobacco industry. The proposed settlement sought to require the tobacco industry to pay $368 billion over 25 years for smoking-related medical costs incurred by the states and fund tobacco control programs and research. It also sought to limit tobacco sales and stop advertising with characters such as the Marlboro Man and Joe Camel. In exchange, the FDA would have to refrain from regulating nicotine, and the industry would become immune from further liability lawsuits. The settlement also required Congress to enact a new law implementing its terms.

To Rep. Waxman and others in Congress, the proposed settlement offered far too much for far too little. A bipartisan group helped to establish the Advisory Committee on Tobacco Policy and Public health, co-chaired by former U.S. Surgeon General Koop and former FDA Commissioner Kessler, to advise Congress on the settlement. The advisory committee released its final report in July 1997, which laid out a much more comprehensive tobacco control program and recommended much tougher regulation, weakening congressional support for a bill implementing the proposed settlement.[21]

In 1998, Rep. Waxman released 81 R.J. Reynolds documents, dated 1973 to 1990, obtained from law firms that had sued the company for marketing to children via the Joe Camel campaign. The documents included a 1974 presentation in which the company’s marketing vice president said of young smokers: “They represent tomorrow’s cigarette business. As this 14 – 24 age group matures, they will account for a key share of the total cigarette volume for at least the next 25 years.”[22] A 1975 memo stressed that “to ensure increased and longer-term growth for Camel Filter, the brand must increase its share penetration among the 14 – 24 age group.”[23] A 1985 research report testing Joe Camel ads found they were well received by focus groups of 18 – 24 year olds, while cautioning they also “may be appealing to an even younger age group.” In response, the Justice Department reportedly began investigating whether tobacco firms had committed perjury when testifying they had never deliberately marketed to children.

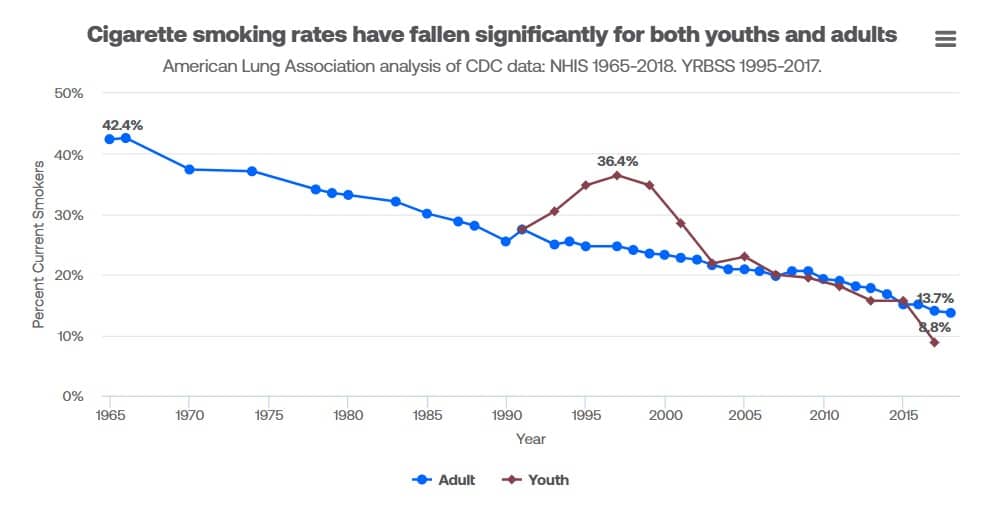

As Congress continued to expose the tobacco industry’s deceptions, marketing misconduct, and harmful products, public opinion turned increasingly against smoking. Statistics show cigarette smoking by American adults decreased from 42.4% in 1965, to 20.6% in 2009, and has continued to fall. Smoking rates among American youth are now below 10%.[24]

Congressional efforts to regulate tobacco products also continued. In 1998, Rep. Waxman worked with Rep. Bliley, a tobacco supporter and then chair of the Energy and Commerce Committee, on comprehensive tobacco legislation, but their bill never received a House vote. In 2004, on a vote of 78-15, the Senate passed a bipartisan bill sponsored by Sens. Mike DeWine of Ohio and Ted Kennedy of Massachusetts to authorize the FDA to regulate tobacco products and buy out struggling tobacco growers, but the House again failed to allow a vote.[25] Finally, on June 22, 2009, Congress passed a landmark bill, the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act, which gave FDA clear authority to regulate the manufacturing, advertising, and sale of tobacco products. Rep. Waxman had authored the bill, led the fight for its enactment, and attended the White House ceremony where President Barack Obama signed it into law.

Rep. Waxman didn’t act alone in his battle against Big Tobacco. His many congressional allies included Senators Dick Durbin (D-IL), Frank Lautenberg (D-NJ), Richard Lugar (R-IN), and Ron Wyden (D-OR) as well as Reps. Tom Davis (R-VA), James Hansen (R-UT), and Mike Synar (D-OK). But it was Rep. Waxman who spearheaded the 25-year oversight effort to expose the health hazards of tobacco and empower the FDA to safeguard the public’s health. His ultimate success demonstrates how one committed Member of Congress can use oversight tools to effect change.

When Rep. Waxman announced that he would retire after the 2014 congressional session, the president of the Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids, Matthew Myers, wrote:

Today, we take it for granted that most Americans understand the truth about the dangers of tobacco use and the deception of the industry. The sea change on smoking in our country wouldn’t have happened without the courage and tenacity of Henry Waxman …. When no one else in Congress dared to take on Big Tobacco, Henry Waxman conducted scores of hearings on the industry. … America owes Henry Waxman a profound debt. He put the lives of the American people ahead of politically powerful special interests.[26]

Learn More

- Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act – An Overview (FDA)

- Henry Waxman Oral History (Edward M. Kennedy Institute)

- Henry A. Waxman’s Record of Accomplishment

- State of Tobacco Control (American Lung Association)

- Timeline: Inside the Tobacco Deal (PBS Frontline)

- Addiction Incorporated (documentary)

Listen to the latest episode of the Levin Center’s podcast, Oversight Matters, with Phil Barnett, who served as the staff director of the House Energy and Commerce Committee and Oversight and Government Reform Committee during his 25 years on Capitol Hill!

* The views expressed on Oversight Matters do not necessarily represent the views of Wayne State University or Wayne State Law School.

C-SPAN Series "Congress Investigates" on the 1994 Tobacco Industry Hearings

Featuring the Levin Center’s Washington, D.C., Director, Elise Bean

[1] State of Tobacco Control. (2022). Tobacco control milestones. American Lung Association. https://www.lung.org/research/sotc/tobacco-timeline

[2] Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. (1993, August 27). Cigarette smoking-attribute mortality and years of potential life lost – United States, 1990. Center for Disease Control. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/00021441.htm

[3] Health Effects of Smokeless Tobacco: Hearings before the Subcommittee on Health and the Environment of the Committee on Energy and Commerce (Serial No. 99-41) 99th Cong. (1985), p. 61. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015021956811

[4] Waxman, H. A. (2009). The Waxman report: How Congress really works [eBook edition].

[5] Freedman, A. M., & Cohen, L. P. (1993, February 11). How cigarette makers keep health question ‘open’ year after year. Wall Street Journal.

[6] PBS. (2014). Inside the tobacco deal. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/settlement/timelines/fullindex.html

[7] Waxman, H. A. (2009).

[8] Regulation of tobacco products (part 1): Hearings before the Subcommittee on Health and the Environment of the Committee on Energy and Commerce (Serial 103-149), 103rd Cong. (1994), p. 527.

[9] In 1962, Winston tobacco company televised a cigarette commercial featuring the cartoon Flintstones. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NAExoSozc2c

[10] Regulation of tobacco products (Serial 103-149), p. 619 – 620.

[11] Regulation of tobacco products (Serial 103-149), p. 685 – 690.

[12] Regulation of tobacco products (Serial 103-149), p. 528.

[13] Regulation of tobacco products (part 2): Hearings before the Subcommittee on Health and the Environment of the Committee on Energy and Commerce (Serial 103-153), 103rd Cong. (1994), p. 16.

[14] Regulation of tobacco products (Serial 103-153), p. 23 – 27.

[15] Waxman, H. A. (2009).

[16] Waxman, H. A. (2009).

[17] Morton Rosenberg (2017). When Congress Comes Calling. p. 315; Glantz, S. A., Slade, J., Bero, L. A., Hanauer, P., & Barnes, D. E. (1996). The Cigarette Papers. University of California Press. p. 8.

[18] Regulation of tobacco products (part 3): Hearings before the Subcommittee on Health and the Environment of the Committee on Energy and Commerce (Serial 103-171), 103rd Cong. (1994), p. 86.

[19] Regulation of tobacco products (Serial 103-171), p. 139.

[20] 104 Cong. Rec. 20367 (1995).

[21] Waxman, H. A. (2009).

[22] Mintz, J., & Torry, S. (1998, January 15). Internal R. J. Reynolds documents detail cigarette marketing aimed at children. Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/national/longterm/tobacco/stories/memos1.htm

[23] Mintz & Torry (1998).

[24] American Lung Association. (2018). Cigarette smoking rates have fallen significantly for both youths and adults [Graph]. https://papersowl.com/discover/overall-tobacco-trends

[25] Shatenstein, S. (2004). Food and Drug Administration regulation of tobacco products: Introduction. Tobacco Control, 13(4), p. 438.

[26] Myers, M. L. (2014, January 30). Henry Waxman showed American the true face of the tobacco industry. Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids. https://www.tobaccofreekids.org/press-releases/henry_waxman_showed_america_the_true_face_of_the_tobacco_industry