If you’ve ever wondered if legislative oversight is really that important, prepare to change your mind.

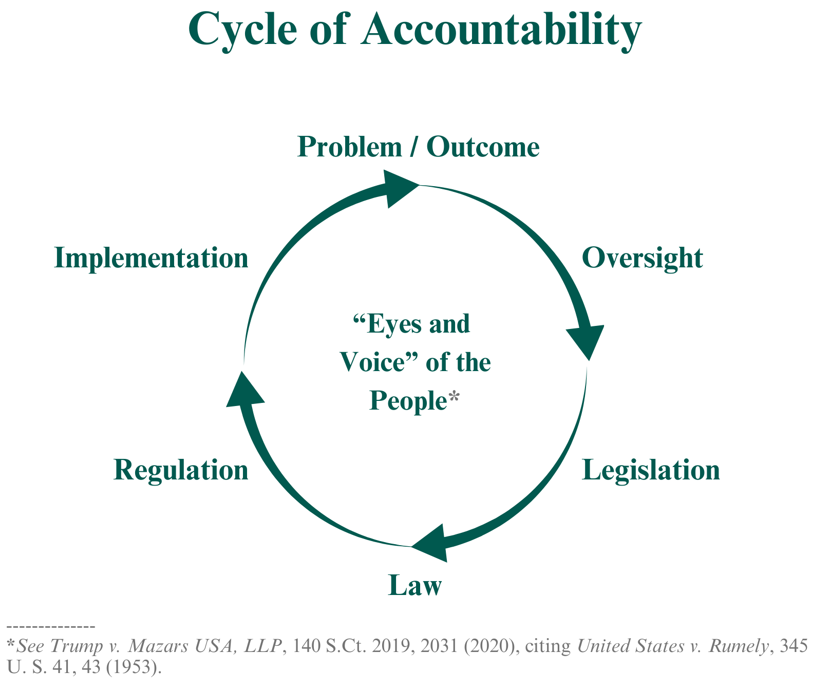

When we speak about oversight at the State Oversight Academy, we often discuss the Cycle of Accountability, a way of depicting the legislative process when it is at its most effective and accountable. The legislature identifies a problem and performs oversight by reviewing documents, interviewing witnesses, holding hearings, and issuing reports that summarize its findings and recommend steps for addressing the problem. Then, if necessary, the legislature passes a bill that becomes law. This usually leads to the issuance of regulations which are then implemented.

But the cycle doesn’t stop there. Many major policy problems can — and do — reveal themselves in implementation, making it crucial for legislators to continue overseeing the process to ensure that a) the law is being applied as intended and b) that the law itself is the best response to the problem. If that isn’t true, the legislature must take corrective action.

This week, the Texas legislature is doing so in dramatic – and seemingly unprecedented – fashion.

Just 24 hours before Robert Roberson was scheduled to be executed for the 2002 death of his young daughter, Nikki Curtis, the House Committee on Criminal Jurisprudence issued a legislative subpoena for the death row inmate. The subpoena argues his testimony is essential to understand how the Texas 2013 ‘junk science’ law, which allows redress for those convicted of crimes based on science no longer considered credible, failed in implementation. In Roberson’s case, evidence was presented that his daughter died of shaken baby syndrome, which many physicians now consider to be a questionable diagnosis. Medical experts who reexamined the case believe that Nikki died of natural causes. However, the Court of Criminal Appeals ruled the junk science law did not apply to his case, although it ordered a new trial for another case that hinged on evidence of shaken baby syndrome this month. Nationwide, at least 32 people have been exonerated in shaken baby cases since 1992. If his death sentence is carried out, Roberson will be the first person in the United States executed for a shaken baby syndrome case.

In a filing before the Texas Supreme Court regarding a potential separation of powers issue, attorneys for the House committee wrote, “This is a matter of the highest constitutional importance because it involves a core legislative function . . . committee investigations and inquiries are a direct exercise of the lawmaking power textually committed to the legislative branch.” The Court sided with the committee and issued a stay of execution so Roberson could appear at the hearing.

In addition to this bold action, a bipartisan group of more than 85 legislators sent letters to Governor Greg Abbott in September urging clemency for Roberson. Gov. Abbott submitted an amicus brief the morning of the hearing, contending that the committee violated the Separation of Powers Clause by essentially granting clemency to Roberson, a power exclusively held by the governor. The hearing, scheduled to begin at 12pm CT, started nearly an hour late when Rep. Joe Moody, chair of the House Committee on Criminal Jurisprudence, announced that Roberson would not testify while these legal issues were being negotiated. The committee is now working with the executive branch to arrange for Roberson’s in-person testimony, including, as Rep. Jeff Leach told CNN, a potential “field trip . . . to interview him in a public hearing there at the prison.”

Rep. Brian Harrison addressed the lawsuits brought against the committee in his opening statement: “If the Legislature can’t exercise oversight over a potential breach of a duly enacted statute that may result in the government taking an innocent person’s life, then there is no subject matter by which the Legislature can exercise oversight. This may be the most quintessential and core function of the Legislature.”

“When the legislature passes a law and finds out that it’s not working the way that it was intended to, it is incumbent upon us to step in and make that law right,” said Rep. Moody.

Reps. Harrison and Moody are correct. While this is a sensational example of legislative oversight, it is true of every law. Government actions affect citizens’ lives every day, and while they aren’t generally life and death decisions, if they are not implemented as intended, they can be harmful. In Robinson’s case, the U.S. Supreme Court “is powerless to act without a colorable federal claim,” so his fate rests with Texas. Guilt or actual innocence is not the question before the committee; it is whether the law is being implemented as the legislature intended.

While the committee’s actions seem extraordinary, that is largely contextual. The legislative subpoena is a tool provided to committees in many states and Congress to utilize in oversight investigations. Subpoenas can be used to obtain financial records from a state agency, disciplinary reports from a state prison – or, it turns out, to save a life.

Proper legislative oversight is critical, and the State Oversight Academy is watching this remarkable investigation closely.